It started with a metal box of old slides. A forgotten relic tucked away in the attic, its edges worn from time. The photographic evidence of a Grand European tour, almost a relic in itself these days. No longer do young adults get sent to the continent to be educated in culture, a clear loss for the American youth. Pictures of canals in Amsterdam, the Heineken bottling factory, beautiful gardens, and forgotten side streets. And then, suddenly, there it was—Notre-Dame.

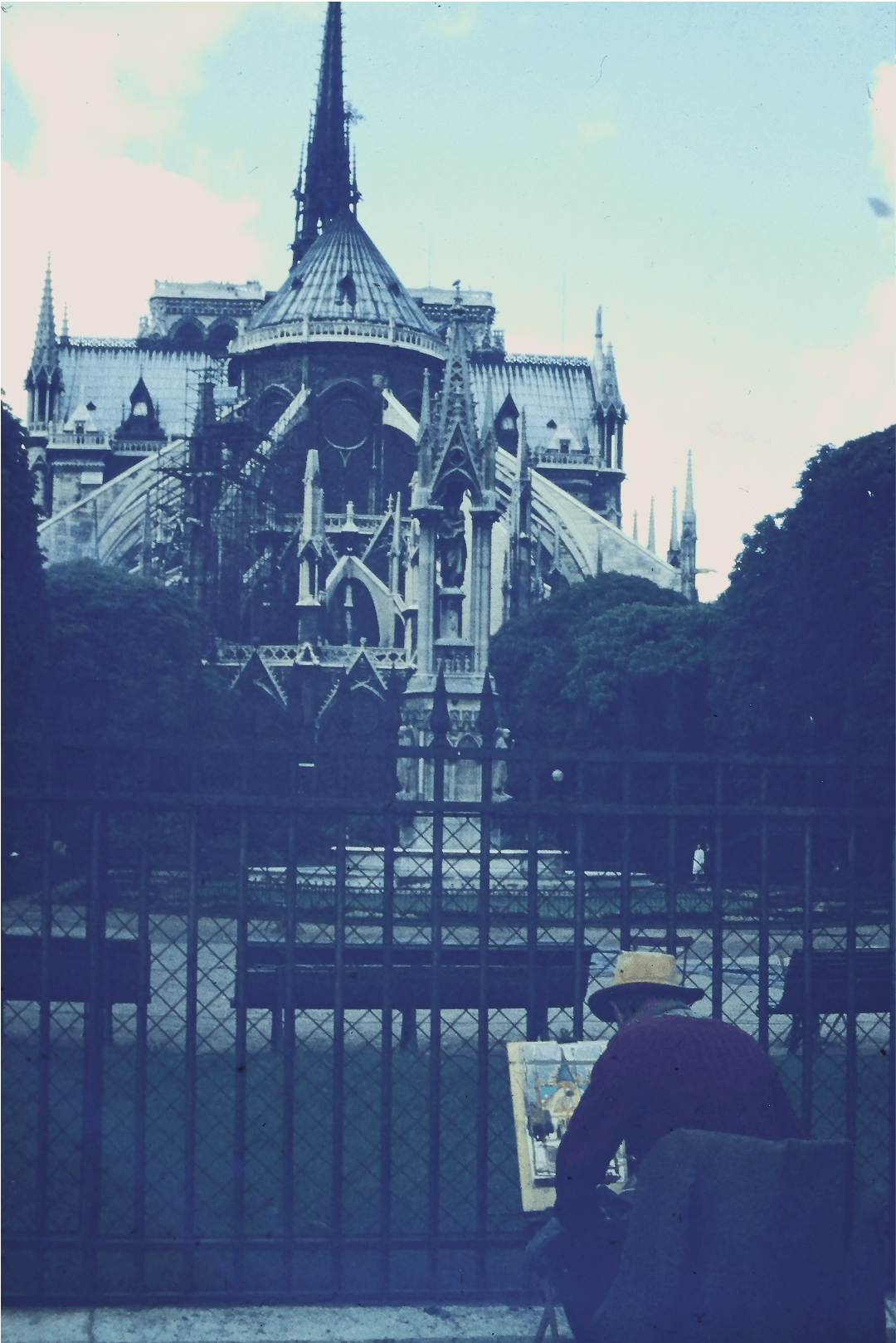

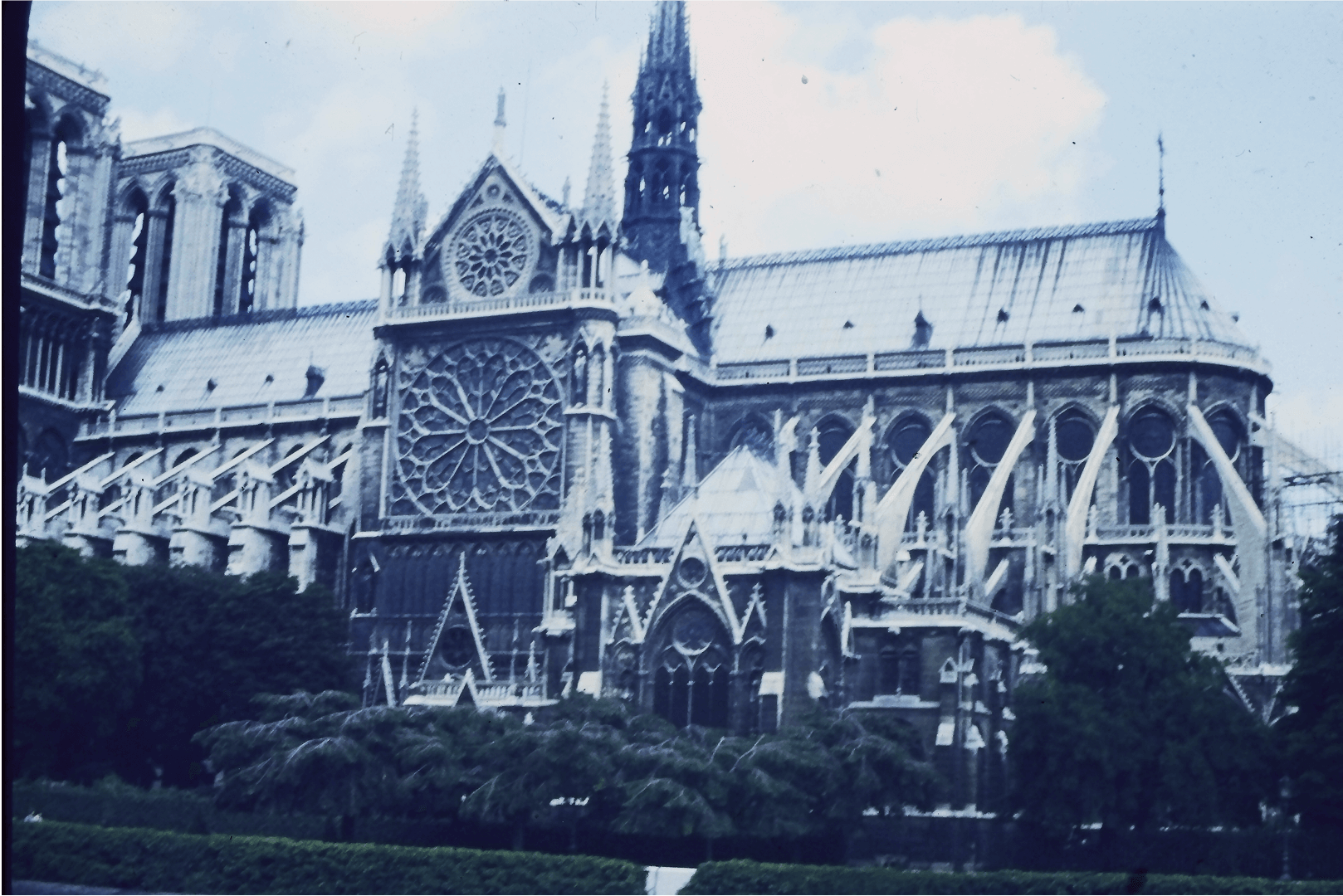

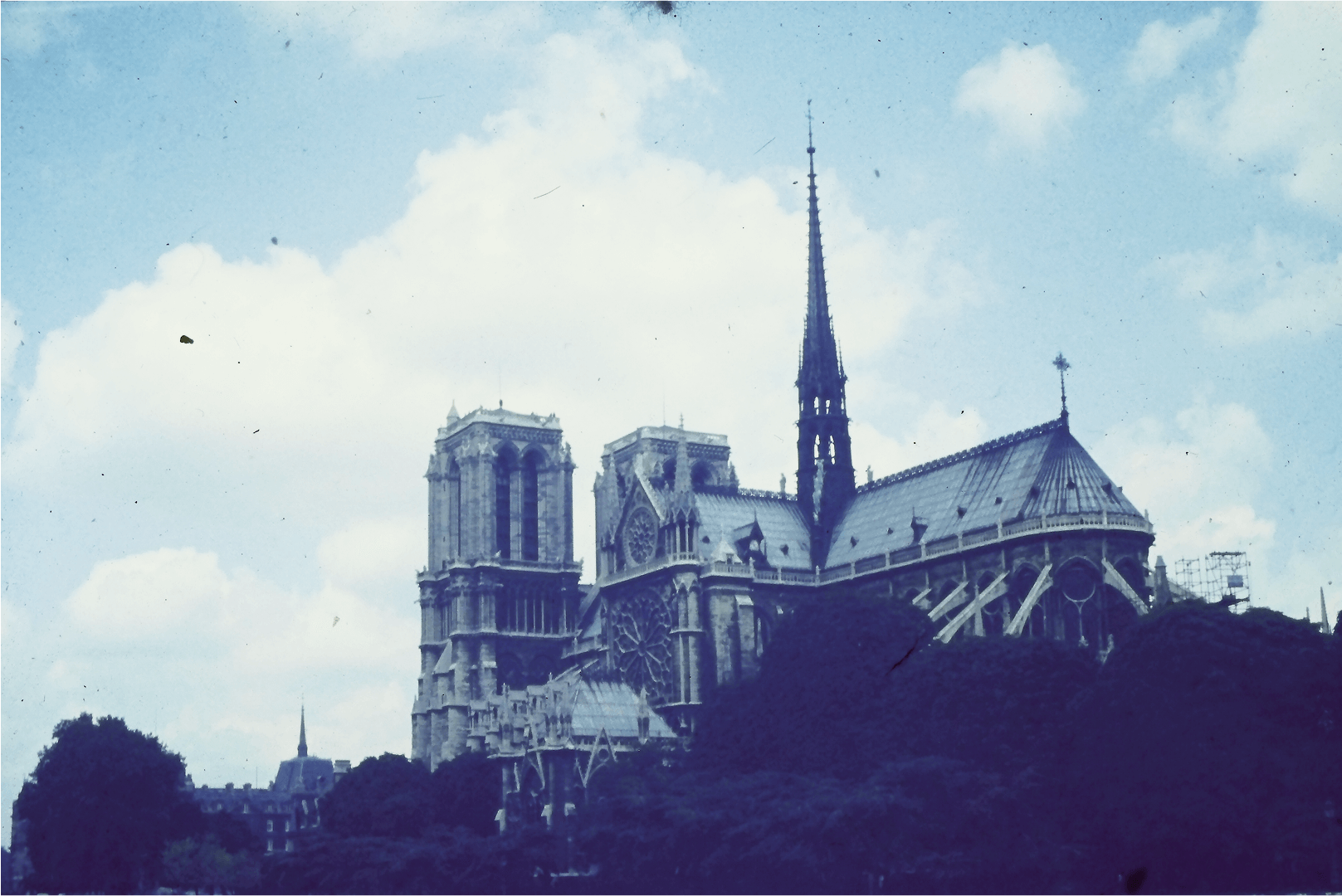

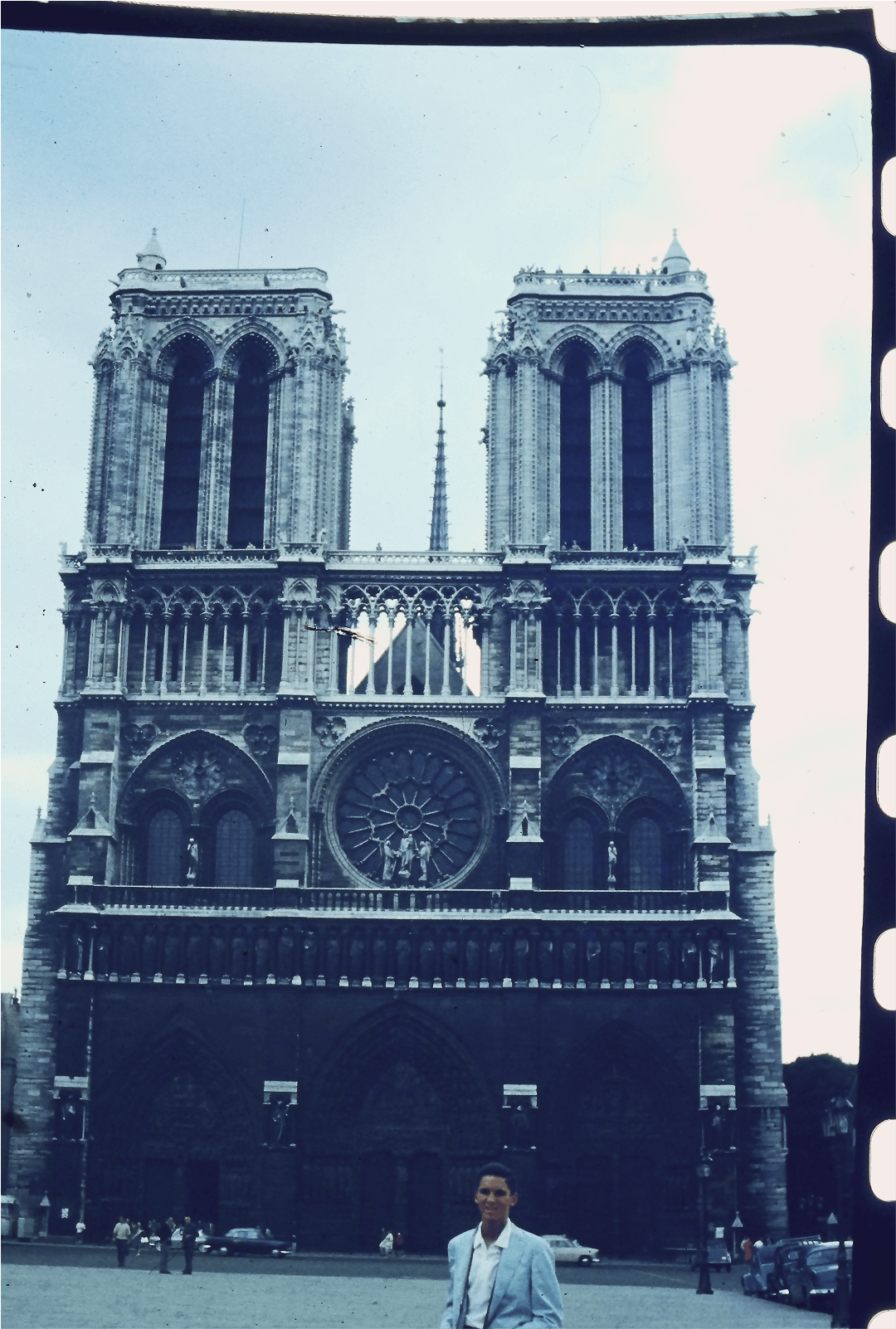

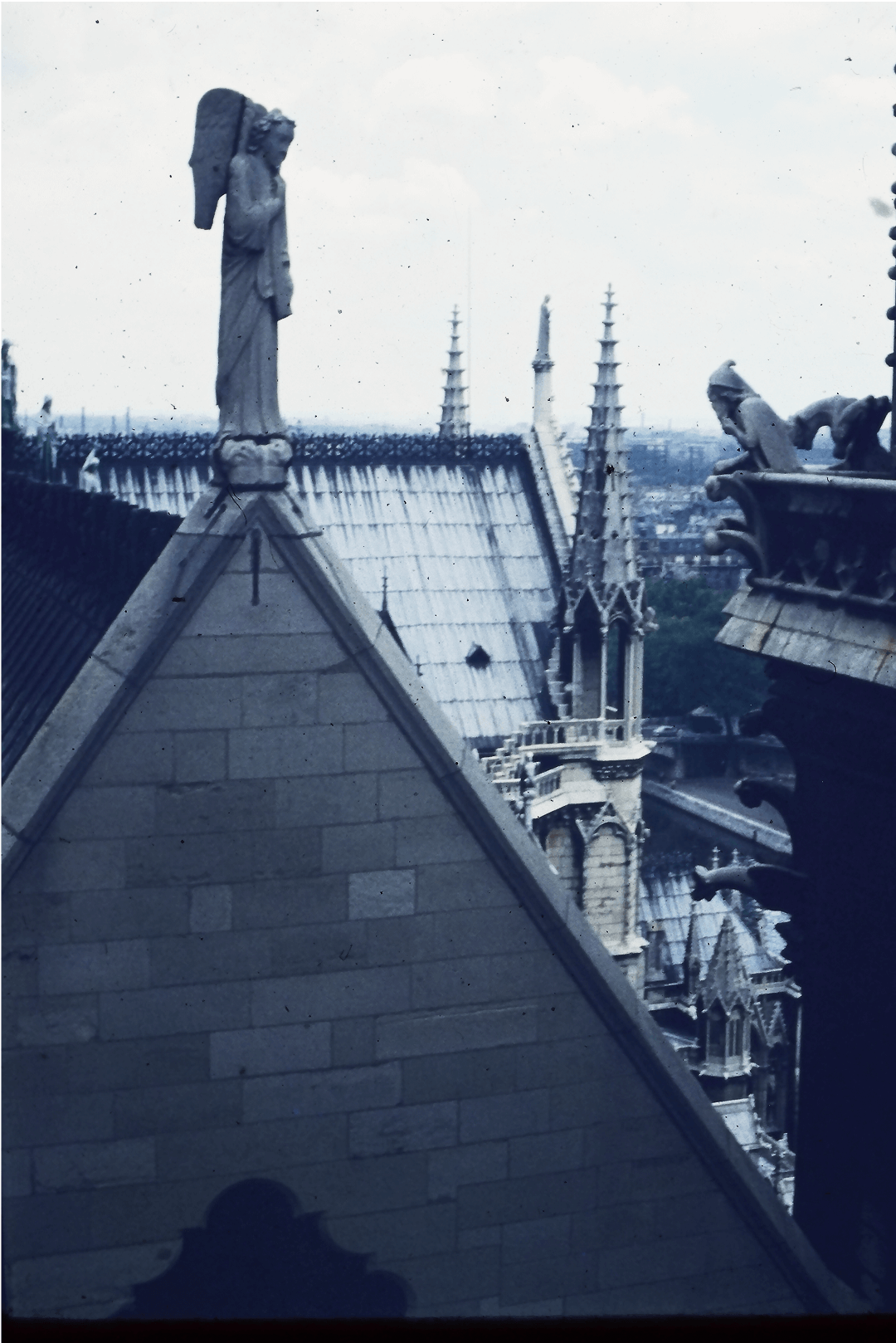

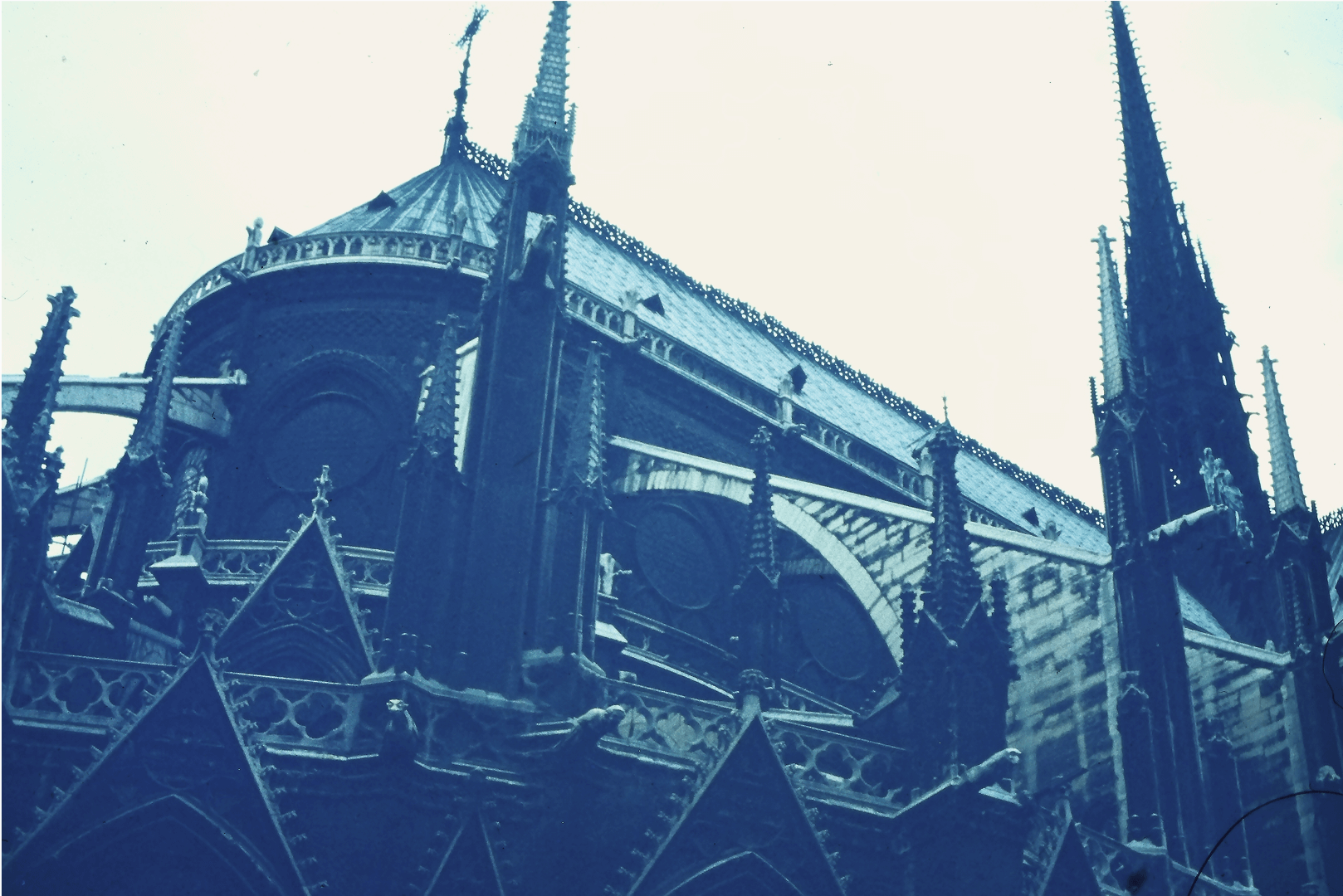

The photos, taken in the early 1960s, were unmistakable: the towering façade, the intricate stonework, the sharp silhouette of the spire against the Parisian sky. The person who had taken this photo had captured something more than just a structure. They had preserved a moment in time, a piece of history frozen in light and shadow. Even through the imperfection of Ektachrome, the building was breathtaking.

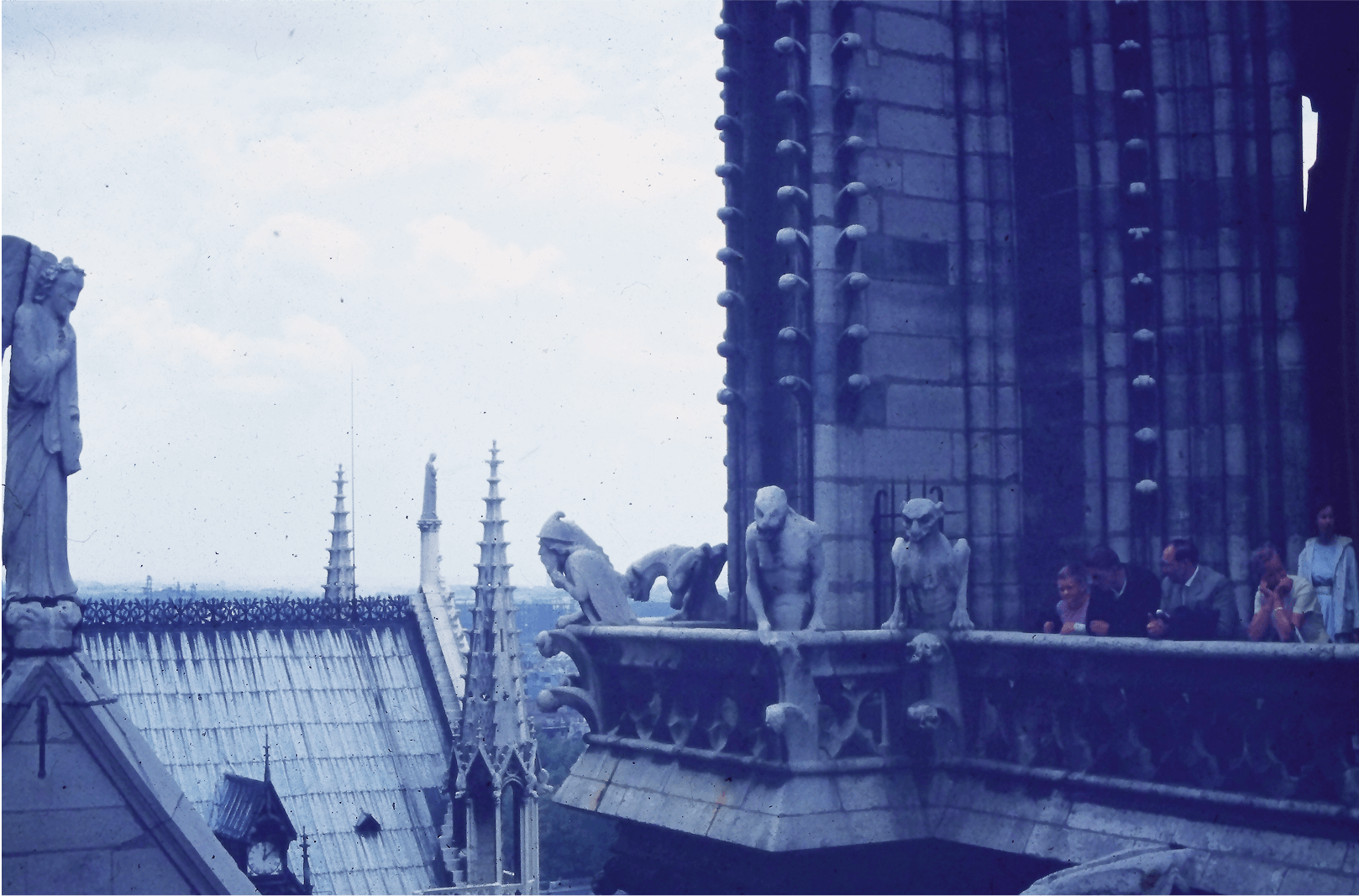

But looking out at the world from atop the roof, one could not help but think about the fires and how blissfully unaware the photographer was that this roof he stood upon would one day disappear into flames as the world watched. The fire of 2019 left the cathedral wounded, its ancient wooden roof consumed in flames, its iconic spire collapsing into the inferno. In its destruction, however, lay a reminder: architecture is not just construction. It is art. And like all great art, it evolves.

What makes architecture an art form? Is it the labor of the artisans who carve stone and set beams? The vision of the architect who first sketches an idea? Or is it the final masterpiece itself—a structure that, once completed, takes on a life of its own?

Notre-Dame, like all great cathedrals, is the result of generations of artistic ambition. The original architect remains unknown, their name lost to time. But their vision was revolutionary and inspired and continues to inspire. They imagined a place where light and stone intertwined, where the divine could be made tangible through craftsmanship.

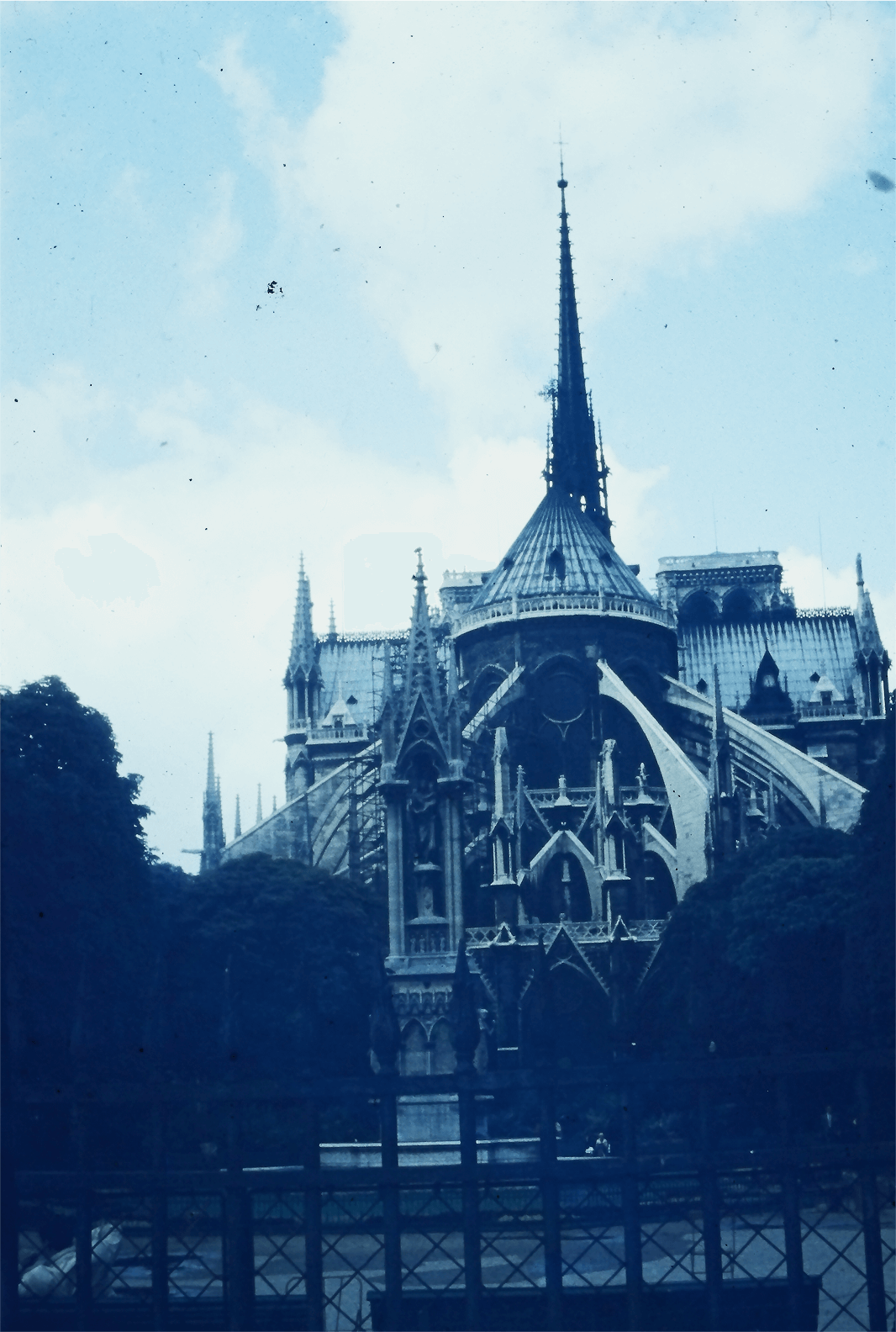

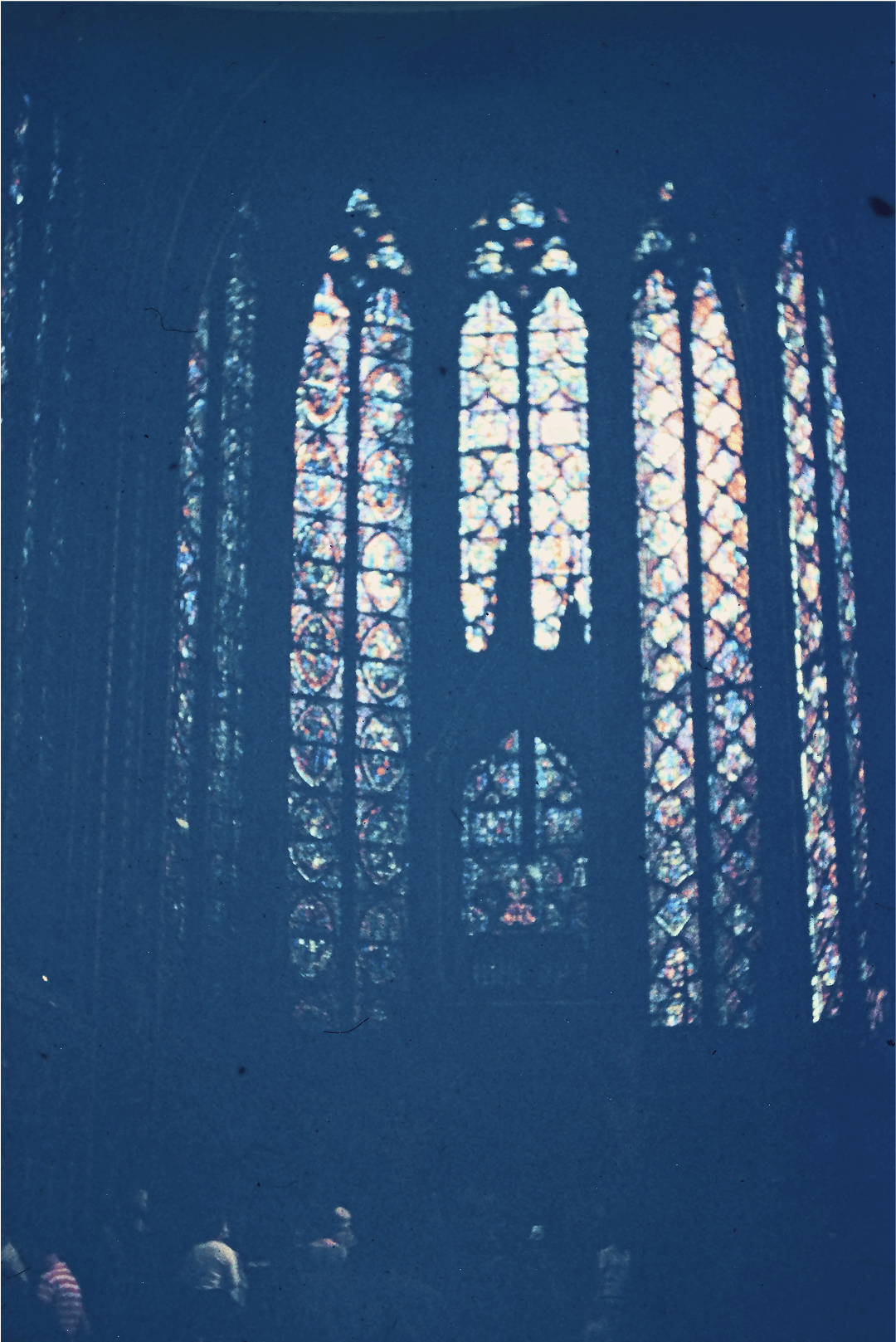

As the cathedral grew, so did the list of artists who shaped it. From the stained-glass artisans of the 13th century who created its famed rose windows to the sculptors who chiseled gargoyles and saints into its façade, Notre-Dame became a canvas for hundreds of hands. Each addition, each restoration, layered the cathedral with new meaning, new interpretation.

By the time the 19th century arrived, Notre-Dame had suffered greatly—wars, neglect, and revolutions had left it battered and forgotten. It was Eugène Viollet-le-Duc who stepped in, a man whose vision for restoration was as bold as the original builders'. But was he restoring Notre-Dame, or was he creating something entirely new?

Viollet-le-Duc did not just repair what had been lost—he reimagined it. His most famous contribution, the towering spire, was not a faithful reproduction of its medieval predecessor but an interpretation of what he believed should have been there. He introduced sculpted apostles, ornate embellishments, and a verticality that was even more extreme than the original design.

So at what point does restoration become reinvention? How much can an artist or artisan alter a work before it ceases to be the same piece? If Notre-Dame had simply been rebuilt exactly as it was, would it still hold the same artistic power, or would it become a mere replica of itself?

This question is being asked again today as Notre-Dame undergoes its most ambitious restoration yet. Following the fire, experts debated whether to recreate the cathedral as it was or to embrace a modern reinterpretation. Ultimately, they chose to honor the vision of the past, reconstructing the wooden framework using medieval techniques and sourcing ancient oak trees to mirror the original roof. The craftsmen rebuilding Notre-Dame are not merely duplicating; they are actively preserving and reinterpreting.

Among those invited to help preserve this structure are teachers of the North Bennett Street School (NBSS) in Boston, Massachusetts. Originally started to help teach the immigrant children arriving daily with trades to support themselves. Today the school continues these practices, offering traditional skills like woodworking, timber framing, bookbinding, jewelry making. They work in conjunction with Boston Architectural College and their historic preservation department. Teachers at NBSS, Michael Burrey and Jackson Dubois were invited to the Asselin facility in Thouars, France to work on the greatest preservation project either had ever seen.

Perhaps this is the final proof that art is never truly finished. Notre-Dame has never been a single, static creation—it has been built, rebuilt, and reshaped over generations, carrying the hands of countless artists along its walls. And when its doors reopen, when light once again filters through its vaulted ceiling, it will stand not as a relic of the past, but as an ongoing masterpiece—one that, like all great works of art, continues to evolve.

And just like Notre-Dame itself, those old slides tell a similar story. Although they were never intended to be art, they have become just that. The perspective of the photographer, the fleeting moment captured decades ago, is now something to be savored, appreciated, and remembered. Art is not always created with intention—it is often discovered, cherished, and given new meaning with time. The slides, much like the cathedral, prove that nothing is ever truly finished, and beauty continues to be found in what remains.